Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Wednesday Comedy: Michele Bachmann

Most everyone is by now aware of US presidential candidate Michele Bachmann's recent comments regarding the true significance of this year's America-affecting natural disasters (I don't what she thinks of those natural events that have occurred countless times elsewhere in the world):

Bachmann claims she was joking, but I don't believe she was. No, she was scoring cheap political points before a crowd that saw nothing wrong or inconsistent at all in her statements.

Evidently, Bachmann believes she can recognize divine messages and decipher them for us. I guess that's how it works: God strikes down a shitload of communities in the Atlantic and then up the US eastern seaboard because he wants to let one presidential candidate know that He thinks too many people are on welfare and social security.

It's all about Bachmann, after all. The Lawd communicates with her by decimating folks, and she delivers unto us the good news.

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

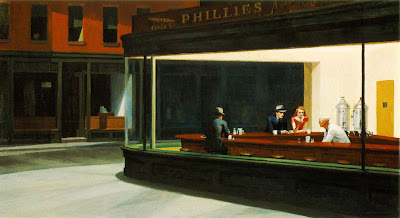

Larry the Nighthawk

Very excited to have purchased tickets to see The Bad Plus at the Regattabar in Boston. I'll be at the 28 October late show--10:00 PM!--along with my father and my brothers.

If you are in the neighborhood, stop by and say hello! Tickets are only $25.00.

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

Return of the Teacher

Somehow, I missed this afternoon's earthquake. I was probably too engrossed in finishing the syllabus for my introduction to literature course. Class begins next week, marking my return to the classroom after more than a year doing doctoral student stuff.

Students should find the class enjoyable and useful. See what you think. Here's the reading plan for the term, subject to further change:

Unit 1: Drama

An Introduction to Drama

Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 1

William Shakespeare, Life and Works

Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 2

Hamlet: Sources and Influence

Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 3

Hamlet: Texts and Authorship

Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 4

The Shakespearean Stage

Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 5

Drama (Literature) as a Mirror, Part 1

Ibsen, A Doll’s House, Act 1

Drama (Literature) as a Mirror, Part 2

Ibsen, A Doll’s House, Act 2

Drama (Literature) as a Mirror, Part 3

Ibsen, A Doll’s House, Act 3

Drama (Literature) and Redemption, Part 1

Wilson, Fences, Act 1

Drama (Literature) and Redemption, Part 2

Wilson, Fences, Act 2

Unit 2: Poetry

Sound and Sense: An Introduction to Poetry

Shakespeare, Sonnet 18

Kinnell, "The Bear"

Shakespearean Sonnet (and One Spenserian)

Shakespeare, Sonnets 73 and 130

Keats, “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be"

McKay, “America"

Spenser, “One Day I Wrote Her Name upon the Strand"

Petrarchan Sonnet

Donne, "Death, Be Not Proud"

Milton, "When I Consider How My Light Is Spent"

Wordsworth, "The World Is Too Much With Us"

Browning, "How Do I Love Thee?"

Other Sonnets

Shelley, "Ozymandias"

Hopkins, "Pied Beauty"

Yeats, "Leda and the Swan"

cummings, "pity this busy monster,manunkind"

Blank Verse

Yeats, "The Second Coming"

Frost, "After Apple-Picking"

Frost, "Birches"

Stafford, "Traveling through the Dark"

Ode

Wordsworth, "Ode: Intimations of Immortality"

Shelley, “Ode to the West Wind"

Keats, “Ode on a Grecian Urn"

Villanelle (and a Pantoum)

Bishop, "One Art"

Thomas, "Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night"

Hacker, "Villanelle"

Jeffers, "Outlandish Blues (The Movie)"

Open Form

Whitman, “A Noiseless Patient Spider"

Moore, “Poetry"

Duncan, “The Torso"

Silko, “Prayer to the Pacific"

Elegy

Jonson, "On My First Son"

Gray, "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard"

Housman, "To An Athlete Dying Young"

Ransom, "Bells for John Whiteside’s Daughter"

Hill, "In Memory of Jane Fraser"

Dramatic Monologue

Tennyson, “Ulysses"

Browning, “My Last Duchess"

Eliot, "Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock"

Faith and Doubt

Herbert, "Easter Wings"

Lowell, "Skunk Hour"

Kumin, "Credo"

Kenyon, "Let Evening Come"

Conformity and Rebellion

Dickinson, "Much Madness Is Divinest Sense"

Brooks, "We Real Cool"

Sanchez, "An Anthem"

McHugh, "What He Thought"

Fractured Fairy Tales

Sexton, "Cinderella"

Piercy, "Barbie Doll"

Fulton, "You Can’t Rhumboogie in a Ball and Chain"

Duhamel, "One Afternoon When Barbie Wanted to Join the Military"

Animals

Blake, "The Tyger"

Millay, "Wild Swans"

Bishop, "The Fish"

Hall, "Names of Horses"

Harjo, "She Had Some Horses"

Childhood

Roethke, "My Papa’s Waltz"

Hayden, "Those Winter Sundays"

Thomas, "Fern Hill"

Bukowski, "My Old Man"

Willard, "Questions My Son Asked Me, Answers I Never Gave Him"

Carpe Diem

Herrick, "To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time"

Marvell, "To His Coy Mistress"

Housman, "Loveliest of Trees, the Cherry Now"

O’Hara, "The Day Lady Died"

Unit 3: Short Fiction

Characters, Part 1Students should find the writing requirements manageable: five short essays, freewriting exercises, an annotated bibliography, and a research paper.

Bambara, "The Lesson"

Characters, Part 2

O’Connor, "A Good Man Is Hard to Find"

Characters, Part 3

Carver, "Cathedral"

Characters, Part 4

Tan, "Two Kinds"

Plots, Part 1

Poe, "The Cask of Amontillado"

Plots, Part 2

Fitzgerald, "Winter Dreams"

Plots, Part 3

Hemingway, "Hills Like White Elephants"

Plots, Part 4

Oates, "Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?"

Settings, Part 1

Hawthorne, "Young Goodman Brown"

Settings, Part 2

Garcia Marquez, "A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings"

Settings, Part 3

Atwood, "Death by Landscape"

Let's go!

Thursday, August 18, 2011

A Bad Argument by C.S. Lewis

Although C.S. Lewis was a medievalist, among other things, I encountered only The Discarded Image among his writings in the field. He was a scholar of the high and later medieval periods, and I concentrated on the Anglo-Saxon material, so I would have had to pursue him on my own for a fuller familiarity. I'm certain I read The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe when I was a kid. Although I don't remember much of that book itself, I do remember that the fantasy was pretty good.

Lewis is today considered a big deal in Christian evangelical and apologetic circles. A quick glance through notable quotes by Lewis, or a more extended reading through works such as Mere Christianity, reveals why he is held in high esteem by defenders of the faith. He sounds good. He gives a sharp impression of even-handed questioning and reasoning--and of course he comes to the right conclusions that atheism is untenable and that Jesus is God (or isn't not-God).

One brief argument of Lewis's bothers me particularly:

If the solar system was brought about by an accidental collision, then the appearance of organic life on this planet was also an accident, and the whole evolution of Man was an accident too. If so, then all our present thoughts are mere accidents -- the accidental by-product of the movement of atoms. And this holds for the thoughts of the materialists and astronomers as well as for anyone else’s. But if their thoughts -- i.e., of Materialism and Astronomy -- are merely accidental by-products, why should we believe them to be true? I see no reason for believing that one accident should be able to give me a correct account of all the other accidents. It’s like expecting that the accidental shape taken by the splash when you upset a milk-jug should give you a correct account of how the jug was made and why it was upset.This bit comes from "Answers to Questions on Christianity," which can be found in God in the Dock. The main problem is Lewis's unfortunate choice of the word "accident" and its variants--used here an astonishing 9 times in a passage of only 149 words (6%).

Now, "accident" has several senses, including one that invokes chance and the lack of apparent or deliberate cause. So it's a legitimate word for Lewis to use. The unfortunate part is that it's not really accurate in the context of how the solar system was brought about. A more judicious word to use would have been "natural," like so:

If the solar system was brought about by a natural collision, then the appearance of organic life on this planet was also natural, and the whole evolution of Man was natural too. If so, then all our present thoughts are natural -- the natural by-product of the movement of atoms. And this holds for the thoughts of the materialists and astronomers as well as for anyone else’s. But if their thoughts -- i.e., of Materialism and Astronomy -- are merely natural by-products, why should we believe them to be true? I see no reason for believing that one natural by-product should be able to give me a correct account of all the other natural by-products. It’s like expecting that the natural shape taken by the splash when you upset a milk-jug should give you a correct account of how the jug was made and why it was upset.How different Lewis's argument appears with the words substituted! Yes, precisely, the solar system was well within the purview of natural forces in the universe. Yes, the physical parameters of the universe and both the relations and reactions of objects to one another made organic life possible. Yes, the evolution of creatures such as humanity were potential paths allowed by nature. And yes, thinking is natural too.

Lewis really starts to err when he denigrates human thought as being untrustworthy unless it has been given by God. We of course use not only thought but also tools, and tools are artificial--not natural, not accidental. So, even if our thoughts are untrustworthy by themselves--and they are--we have been good enough to develop tools that enhance the depth and breadth of our thought. These tools also augment our abilities to apprehend and understand the universe. From our math and logic to our telecommunications and telescopes, we've been able to grope our way to discriminating reliable from specious thinking.

The milk-splash crack doesn't work either because the shape, positioning, speed, and other factors of a milk splash will provide us lots of information from which to establish hypothesis on the jug's composition and movements.

Obviously, Lewis's apologetic ouvere should not be dismissed on one brief and lousy answer of his. Nevertheless, his answer is quite poor on several levels. It's biased, narrow, and surprisingly unimaginative. Were I a Christian apologist with Lewis's works in my hand, I might invoke the rule of "Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me."

Wednesday, August 17, 2011

Wednesday Comedy: Jesus Loves Nukes

This week's post focuses on something that is funny in an off-kilter and perhaps uncomfortable way.

Below are selected slides from a PowerPoint by US Air Force Chaplain Captain Shin Soh. The 42-slide PowerPoint takes ethics as its subject, and apparently is part of an official training for nuclear missile officers.

The slide below introduces Just War Theory. Presumably, the image to the right is meant to suggest that Roman fighting against the Visigoths was justified. Historically, the sack of Rome was monumentally important not only to Augustine of Hippo and his thinking but also to long-term European politics and culture.

Although the Roman empire may have been right and justified to fight the Visigoth forces, the empire itself had a long and proud history of aggression. The empire had also had some history with Gothic tribes. Had the Romans been slightly more inviting to the "Barbarians," this particular attack on the empire may have been averted.

The attempt to present the US with clean hands over Hiroshima is, well, laughable.

Since this is a comedy post, I won't dwell on Hiroshima/Nagasaki except to say that there are two different questions: (1) Was the US's use of the Atomic Bomb justified from a pragmatic perspective, and (2) Was using the Atomic Bomb morally justified? The slides vaguely and weakly imply that the answer is "yes" to both questions. I disagree with that answer.

The rationalization in the Hiroshima slides reflects a stance articulates by Heinrich Himmler in his October 1943 speech to SS leaders. Himmler made the speech, which was recorded, in Poland after touring the killing centers there. Himmler praises the moral resolve to exterminate the Jews. To him, it's a necessary action for the greater good of the fatherland.

In the US Air Force PowerPoint, Hiroshima is similarly justified, and the courage to use nuclear weapons is praised.

Indeed, one slide links up the Nazis and the US as bound by high moral standards rooted in Christianity. The good Germans passed their nuclear secrets over the the US, rather than the Soviets I guess, because we were all united as Christian soldiers.

The slideshow concludes with an obligatory gesture:

Something tells me that many questions should have emerged as a result of this presentation.

Friday, August 12, 2011

Can Science Explain Art, Music, and Literature? (Part 2)

Some months ago, I criticized an article by philosopher Roger Scruton that argued science was unable to explain art, music, and literature.

I wrote at the time:

Scruton, as I see it, plots art and beauty on the same continuum with gods, free will, and souls. Defenders tell us we cannot explain the categories on the continuum. The categories are beyond our full comprehension, exceeding our language, and greater than the real things that are otherwise their material substance (e.g., religious writings and commentaries, neurons, cells and organelles).At the time, I had a brief dialogue over at Scruton's site. I'd like to go through one of his rejoinders bit by bit. He says:

What's more, Scruton and like-minded thinkers advise us not even to try explaining such categories:

The attempt to explain art, music, literature, and the sense of beauty as adaptations is both trivial as science and empty as a form of understanding. It tells us nothing of importance about its subject matter, and does huge intellectual damage in persuading ignorant people that after all there is nothing about the humanities to understand, since they have all been explained — and explained away.This argument is deeply flawed. I don't accept Scruton as an authority to tell us what disciplines and methods to take seriously. Ultimately, the test of disciplines and methods is the knowledge they produce. In his given examples on music and sense of beauty, Scruton finds the Darwinist explanations "absurd." Fine. That's his opinion. But we need not accept those explanations fully to understand that they (1) are out in the public domain, (2) have some legitimacy, and (3) will ultimately stand or fall based on the collection of more data and the performance of more work in the area.

Another truly odious charge is that a Darwinist line of art or literary study obliterates any other modes of explaining and interpreting. The charge is simply untrue. Humanities studies can be interested in both biological explanations and cultural ones. The development of singing, to take an example from Scruton, seems to me very interesting. I want to know about the biological impulses and struggles that singing expresses, and I want to know about the arrangement of pitched sounds. Why that arrangement? What makes it as powerful as it is? What are its precursors? How has it spread and changed in culture?

It seems clear that the sadness of a piece of music is a property of the music, not of the listener – otherwise why should we take such pleasure in listening to sad music?Scruton is just wrong here: it's not at all clear and it's not true. We take pleasure in listening to music we find sad because we like to act out and simulate emotions. We are like cubs in a litter: their play simulates fighting and hunting because that's what they need to do "for real." We find ways to simulate emotions and empathy because both serve us in response to the unpredictable vicissitudes of life.

A piece of music is not in itself sad. The quality of sadness is not part of the music but a product of the listener's response to pitch, timbre, rhythm, and structure. If you want to argue that sadness is "in" the music then you need to be able to isolate and measure sadness. If you cannot isolate and measure sadness, then on what basis do you claim it's "in" there?

Let's move on to see how Scruton develops his argument.

Minor keys and minor triads are not necessarily sad – everything depends on the musical context.Well, this is what I've been saying!

Just to take a well-known instance: ‘My Favourite Things’, from 'The Sound of Music', in E minor, and one of the happiest songs in the American Song Book. Admittedly, in (sic) changes suddenly to G major at the end; but there is nothing in that song remotely reminiscent of the terrifying E flat minor triad that opens the prelude to 'Götterdämmerung'.All this supports my contention. If Scruton is echoing my points, why on earth would he say that I'm "in deep water here"?

Of course Larry is right that music is something more than the ‘selection and arrangement of pitched sounds’, just as a picture is something more than the selection and arrangement of coloured patches.Is this a typo? I think Scruton really thinks I'm saying that music is nothing more than 'selection and arrangement of pitched sounds.’

What I am actually saying, however, is that the "something more" of music lies in what we bring to listening. We are never passive listeners. We distinguish music by understanding it as expressive; when we assign expressive power to a sound, it becomes distinguished from background noise.

But is there a scientific theory that enables us to pass from the description of the sounds to a description of the music – in other words, to a description of what a musical listener 'hears' in those sounds? I have tried to show that there can be no such theory, since musical organisation involves irreducible spatial metaphors – see 'The Aesthetics of Music', ch. 2.Well, there are psychological and cognitive neurological disciplines that may offer such theories as will satisfy Scruton. But I am at a disadvantage because I am unfamiliar with Scruton's longer argument involving music's "irreducible spatial metaphors."

Yet I also think that raising music's "irreducible spatial metaphors" shows the serious flaw in Scruton's thinking, the flaw I identified and criticized in my earlier post here. As soon as we talk about "irreducible spatial metaphors," we are not explaining the music anymore. We have moved from the physical world to the interior world of human subjectivity.

Scruton, we recall, initially was concerned with explaining music and with saying that science could never come up with such an explanation. But if Scruton is correct, then it's because he wants science to explain something it cannot access, how it feels for a person to experience something. It's not unlike demanding to know what it's like for a computer to crunch a new set of numbers. It's not unlike wondering what the sound is of one hand clapping. It's not unlike wondering how many angels can fit on the head of a pin.

Scruton closes:

But the questions here are vast, and not to be solved by local skirmishes.The questions may be vast, but we should perhaps whittle down the questions to ones that are, at least in principle, answerable.

Thursday, August 11, 2011

If You Build It, He Will Come -- And You Better Not Disagree with Me

|

| Look! The logicians are coming out of the cornfield! |

From a person going by the moniker "Ilion." His logic here, like his blog, requires little comment from me:

[W]e “theists” don’t have to rely on the proposition “God is” as a premise; we can, in fact, derive it as a conclusion of purely ‘natural’ reasoning.I said before that Ilion's logic required little comment from me, but I have some reactions I must share:

Reason itself shows any intellectually honest person that both atheism (the explicit denial that God is) and agnosticism (the mealy-mouthed denial that anything at all can be known, as being the “best” way to deny that God is) are false and untenable positions. Reason itself shows any intellectually honest person that, at a minimum:

1) there is a God, who is the Creator;

1a) he is uncaused and is the cause of all that is not-God;

2) he is personal (he is not an impersonal “force” or “principle”);

2a) he is an agent: he knows, and wills, and he acts freely;

3) he is good;

3a) the goodness we grasp comes from, and has its meaning in, his character and being;

4) he intentionally caused/causes “the universe” to be;

4a) he is “outside” time-and-space;

Reason itself shows any intellectually honest person that even if the specifically Christian doctrines about God were false, atheism always was and always will be false. [Re-formatted for clarity.]

- Pity Ilion apparently feels his claims are already supported and require no further defense, for reason itself does not in fact show atheism or theism to be false or untenable.

- Evidently, one must already have read and agreed with the oh-so-sophisticated philosophers and theologians Ilion has in mind. One who hasn't is shit-out-of-luck, I guess.

- Now, I have passing familiarity with Augustine, Anselm, Aquinas, Ockham, Plantinga and others. I find their arguments fascinating but finally too flawed and detached to be convincing.

- I don't know what specific grounds Ilion has for stating that reason itself shows the falsity of atheism and agnosticism.

- Reason itself does not "show" Ilion's #1-#4. Ilion's just making assertions descended from the beautiful but ultimately wrongheaded ranting of folks such as Thomas Aquinas and C.S. Lewis. Lewis in particular is the arch-sophist. One day, I'll need to post on why I think this is so.

- Ilion's qualifying "intellectually honest" (used twice!) tells us all we really need to know. If you disagree with his assertions then you are intellectually dishonest. If you agree with them, you are intellectually honest. Calling all true Scotsmen, calling all true Scotsmen!

- Ilion's fetish with reason itself indicates he doesn't understand atheism. The atheist position is that reason, or reason itself, is wonderful. But reason carries little weight outside of evidence and a consistent methodology for gathering, assessing, and incorporating evidence. Ilion makes what I call the metaphysician's fallacy, the error that logical assertions alone somehow trump evidence, conflicting evidence, and lack of evidence. The metaphysical apologist says: "I think it, it's logical, and I don't need no stinkin' verification of it!"

- If Ilion really wants to be intellectually courageous, perhaps he will explain how to verify his four main claims empirically.

* * * * *

In fairness, I should provide the following link (I just became aware of it) to a post where Ilion elaborates on his views of atheism and irrationality:

The reality of minds in a material world (thus, every human being who has ever existed) is proof that atheism is false. If atheism were indeed the truth about the nature of reality, then we would not -- because we could not -- exist. But we do exist. Therefore, atheism is not the truth about the nature of reality.Oh, dear. This will not do at all. My notes below:

This is the general form of the argument to support the prior claim --

GIVEN the reality of the natural/physical/material world, IF atheism were indeed the truth about the nature of reality, THEN everything which exists and/or transpires must be wholely (sic) reducible, without remainder, to purely physical/material states and causes.

The explanation/proof is as follows --

This "everything" (which exists and must be wholely (sic) reducible, without remainder, to purely physical/material states and causes) includes our minds and all the functions and capabilities of our minds -- including reason (and, really, not just the individual acts of reasoning that we all engage in, but big-r 'Reason').

Now, specifically with respect to reasoning, what inescapably follows from atheism is that it is impossible for anything existing in reality (that included us) to reason.

When an entity reasons, it chooses to move from one thought or concept to another based on (its understanding of) the content of the concepts and of the logical relationship between them.

But, IF atheism were indeed the truth about the nature of reality, THEN this movement from (what we call) thought to though (which activity or change-of-mental-state we call 'reasoning') *has* to be caused by, and must be wholely (sic) explicable in terms of, state-changes of matter. That is, it is not the content of, and logical relationship between, two thoughts which prompts a reasoning entity to move from the one thought to the other, but rather it is some change-of-state of some matter which determines that an entity "thinks" any particular "thought" when it does.

I leave it to the reader to dwell on the further implications.

This logical implication/consequence of atheism (the one I have explicated) directly denies what we all know to be true about the "cause" of all acts of reasoning. This logical implication/consequence of atheism states an absurdity, namely that we do not, and cannot, reason. Since the stated absurdity is a logical implication/consequence of atheism, therefore atheism is shown to be absurd. Which is to say, necessarily false.

- The top-level claim is: If there were no God, we would not exist. No God, no universe, no us.

- Before this claim, Ilion makes a telling error: "The reality of minds in a material world (thus, every human being who has ever existed) is proof that atheism is false."

- The error lies in conflating minds--a human concept, an invention of the imagination--with the brain--a material organ with working parts and effects.

- There is no reality of minds, only a reality of brains.

- The reality of minds, therefore, counts nothing against the truth or untruth of atheism.

- What's missing? The explanation of why the universe needs (needs, in the philosophical sense) God specifically, and how the explanation can be verified by people.

Surely I have shown exactly how Ilion is mistaken. I leave it to the reader to dwell on the further implications.

Wednesday, August 10, 2011

Wednesday Comedy: Is It Safe?

Just endured two days of dental work. Today's fun was some periodontal surgery. By "fun" I mean "agony."

Monday, August 08, 2011

Bad Ratings

I'm disappointed but not shocked that Standard & Poor's decided to lower the long-term sovereign credit rating of the United States to "AA+."

In their report, S&P say:

We lowered our long-term rating on the U.S. because we believe that the prolonged controversy over raising the statutory debt ceiling and the related fiscal policy debate indicate that further near-term progress containing the growth in public spending, especially on entitlements, or on reaching an agreement on raising revenues is less likely than we previously assumed and will remain a contentious and fitful process. We also believe that the fiscal consolidation plan that Congress and the Administration agreed to this week falls short of the amount that we believe is necessary to stabilize the general government debt burden by the middle of the decade.We can easily unpack these paragraphs and isolate the key issues:

Our lowering of the rating was prompted by our view on the rising public debt burden and our perception of greater policymaking uncertainty, consistent with our criteria (see "Sovereign Government Rating Methodology and Assumptions," June 30, 2011, especially Paragraphs 36-41). Nevertheless, we view the U.S. federal government's other economic, external, and monetary credit attributes, which form the basis for the sovereign rating, as broadly unchanged.

- Growth in public spending, especially on entitlements, needs to be contained.

- Revenues must be raised.

- The recent fiscal consolidation plan is too little and too temporary.

- U.S. policy-making needs to be less contentious, more cooperative, and more productive.

If Saletan is wrong, all three global credit rating agencies will downgrade the U.S., and that rating won't be as high as "AA+."

Wednesday, August 03, 2011

Immoral Atheists

|

| Theists think that atheism is all about partying on. |

Before leaving my home early this morning for work, I met my wife at the front door and remarked how beautiful our two daughters were. The two girls, 8 and 5 years old, were sitting together on the sofa watching TV. A few minutes earlier, I had come upon my three-year-old son playing nicely by himself. He invited me to join him, but unfortunately I had to decline (although I would have liked to play for a few minutes).

This house of mine is full of love...and goodness.

And so I get annoyed when self-proclaimed arbiters of morality deign to point out the moral difference between theists and atheists:

It’s not so much that atheists are immoral, but that immoral people are often atheists. That is, the guy who kicks cats anyway, and fears divine retribution, may resolve his problem by deciding that there is no God and therefore no divine retribution.Assertion 1: Immoral people are often atheists.

Then he goes back to kicking cats in peace. Other atheists don’t like him but what can they do?

Response: The writer refers to no specific immoral people here, but do we need to go any farther than the definitely-theist Anders Breivik to wonder whether we have any real data to suggest that immoral people--however defined--are more likely to be atheist than theist? Would knowing whether prison inmates are by and large theist or atheist be useful in addressing the question? It bears mentioning that to a theist of the Abrahamic sort, sin and immorality were not brought into the world by atheists. Theists may therefore wish to exercise a bit more humility and shame.

Hypothetical 1: That is, the guy who kicks cats anyway, and fears divine retribution, may resolve his problem by deciding that there is no God and therefore no divine retribution.

Response: The logic is awry. If the guy kicks cats "anyway," he would seem not to care about "deciding that there is no God." Besides, wouldn't such a person prefer to decide that God exists to allow for confession of sins, acting sincerely contrite, and then going back to the cat-kicking? The writer also seems to think that people "decide" that God doesn't exist in order to overcome fear of divine retribution. This reasoning seems akin to deciding that one's mother and father don't exist in order to overcome fear of disappointing them: mom and dad either exist or they don't, regardless of one's decision. God's existence, on the other hand, is not only unsupported but possibly unsupportable.

Rhetorical flourish 1: Then he goes back to kicking cats in peace. Other atheists don’t like him but what can they do?

Response: What can they do? They can call the police. They can alert PETA and the SPCA. They can confront him in person or write him a nasty letter. They can mobilize to keep neighborhood cats away from the person. Seems to me atheists have plenty of useful options. The writer displays a profound lack of imagination.

* * * * *

The writer above obviously means to argue that atheism does not stipulate a principle from which one could condemn the actions of a cat-kicker. This argument is correct and completely banal. People construct their principles from several sources: parents, teachers, friends, books, political philosophy, and so on. Being an atheist does not at all prevent one from condemning the cat-kicker.

Equally important is the realization that being a theist does not at all permit one to condemn the cat-kicker. The theist's source of morality is exactly the same as the atheist's: parents, teachers, friends, books, political philosophy, and so on.

What's more, in the real world, where moral choices are expressed in and through activity, cultural institutions are designed to guide ethical behavior. We have laws. We have penal codes. We have informal enforcement: as a kid, did you ever have someone's mother scowl at you for acting too wild? In the real world, immoral behavior can have any number of retributive consequences.

Ans that's why I started this with the lovely picture of my family. I don't fear divine retribution, but I do wish for my family to view me favorably. I do want to be seen as good and fair in their eyes. I do want them to be kind, courteous, brave, and humble.

Those who think atheists are immoral or that immoral people are atheists completely ignore that atheists have actual families and loved ones. They forget that atheists live and work in the real world, subject to the same basic rules of conduct.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)